Most rock/pop acts seem to me to settle into a sound, develop an image, find a following, and keep it all rolling as long as they can. They may even have long followup careers as nostalgia acts, doing the old stuff as long as anyone will listen. Expanding as artists…. maybe not so much.

The musicians I most admire tend to be ones who get outside the comfort zone, who continue growing throughout their careers. I also favor ones who seem to get the power of music to take life, concept, and sentiment to a higher level, as opposed to music that just gets your feet moving, your hips churning, or your hormones rising – or that works you up at the government or simply makes you feel cool to yourself.

Today I hail one of my musical heroes, the universally respected singer-keyboardist-guitarist Steve Winwood, born in 1948 in Birmingham, England. I meant to post this on his birthday, May 12, but I had another deadline.

You hear of so many rockers who started their bands as hipsters and learned music on the job. None of that for Stephen Lawrence Winwood, raised in a musical family and exposed to a wide variety of musical genres. By his teens young Winwood was a very professional keyboardist who could have been a session player in almost anybody’s studio. He also had star power, even if he’s said to be a bit introverted.

Early in his career they called him “Little” Stevie Winwood, and I guess he was. He could have been 14 when he started fronting the Spencer Davis Group. Commencing his career as a blue-eyed-soul prodigy and would-be Ray Charles clone, Winwood had more than just a crush on American R &B; he had remarkable feel, as a singer and keyboardist, particularly on piano and Hammond B3 organ. I’ve listened hard to deep cuts on those old LPs. And that voice! Powerful, funky, soulful… Most Americans who heard 1960s rousers “I’m a Man” and “Gimme Some Lovin” presumed without questioning it that the singer was black.

His success with the Spencer Davis Group would have been a career for most people, but Winwood was already past all that. He fled the musical limitations of the blues/soul genre to form the eclectic rock band Traffic in 1967. It’s as if, with Winwood, the music mattered more than the fame. He was 19.

Traffic hit the scene during the psychedelic era and have been active on and off into the 2000s. While at first Traffic got the rep of a flower-power band, possibly because of their often “light” sound, their musical influences included gospel, jazz, fusion, and folk. In fact, almost every Traffic LP crossed so many genres that I’m not sure there ever really was a Traffic “sound.”

Traffic’s most-commended LP was John Barleycorn Must Die (1970). Basically a blues-rock disc with jazz/prog overtones, it holds one true acoustic ballad that somehow fits on it. Driven by its flute, sax, and layered keyboards, “Barleycorn” so stood out in its guitar-driven age that most rock critics didn’t quite know how to listen to it. (One reviewer of the day had trouble classifying the music as any other than “a structured set of harmonics.”)

Winwood’s appearance in the supergroup Blind Faith and his solo career after it probably need not be mentioned to anyone who’s followed popular music in the last 50 years. Winwood is still regarded as the peak of rock royalty, a musician’s musician whose success with a mass-market was coincidental. No less than old friend and guitar “God” Eric Clapton has long recognized it, sharing stage and billing with Winwood at a special series of tours under the “Crossroads” banner. And Ol’ Slowhand ain’t no dummy.

I admire Winwood’s under-the-radar departures from the all-absorbing genre we call rock. The first was Aiye-Keta (1973), an LP with a pair of African musicians and definitely a flyer for the former singer of Blind Faith. You have to like percussion-driven African music to get into Aiye-Keta; it’s out there even for Afro-pop. But as a musical experiment it’s quite impressive in a young rock star. (If you want to check out my favorite tune on the LP, scoot to: “Irin Ajo” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q2uzCO4gUCg&list=RDQ2uzCO4gUCg&start_radio=1&t=702 .)

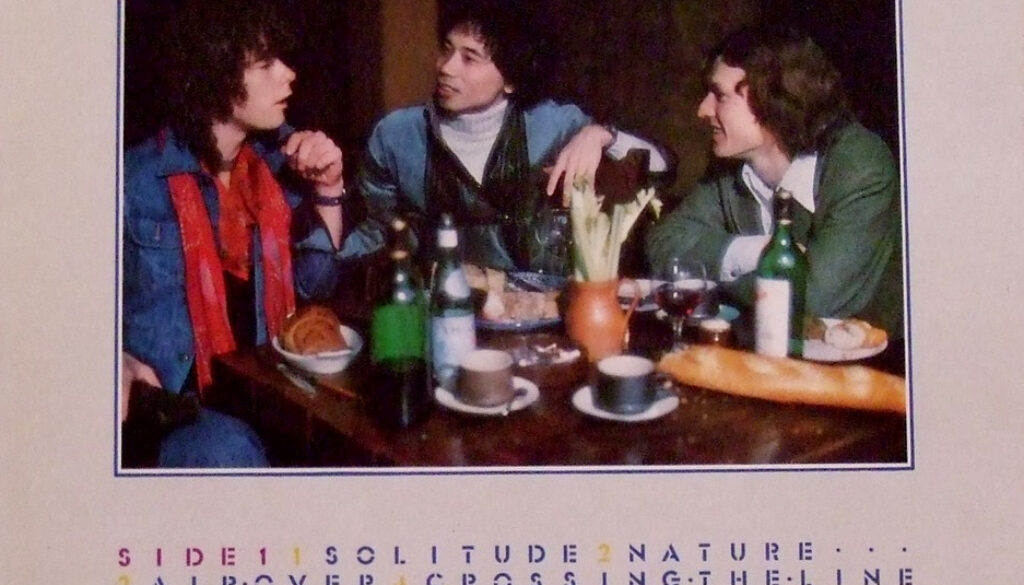

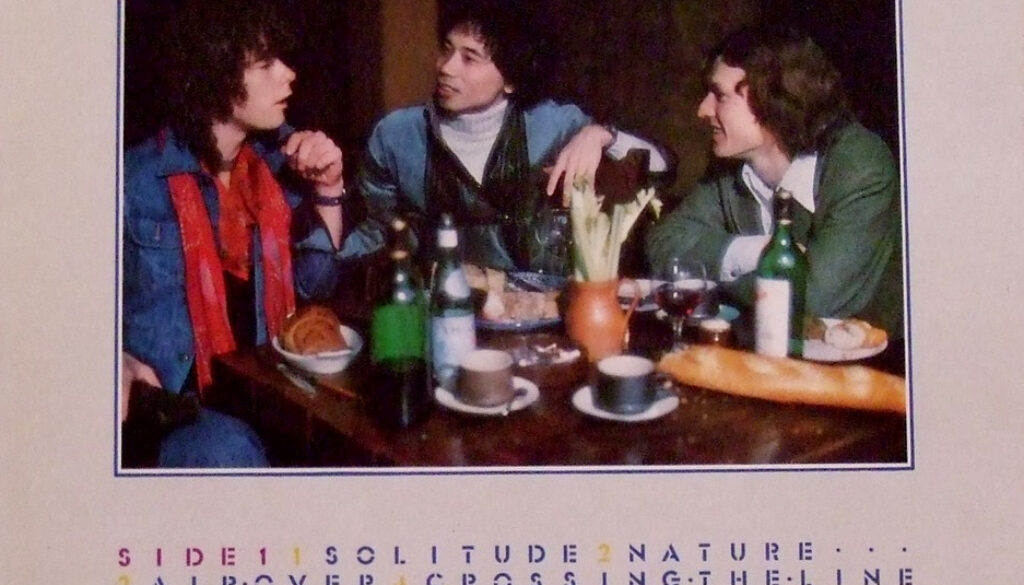

I’m more impressed with Winwood’s collaboration with Japanese composer Stomu Yamashta. The concept album Go (1976) was an LP title and even a project as much as it was a band. While Winwood’s gig with it lasted one LP and one tour, the first incarnation of Go was a fusion supergroup. It included the American jazz guitarist Al Di Meola; ex-Santana drummer Michael Shrieve (later of American prog outfit Automatic Man); and the German prog-synthesizer artist Klaus Schulze, a former member of Tangerine Dream and noted after for collaborations with edgy artists including the wondrous Lisa Gerrard of Dead Can Dance. This is impressive company for a one-time blues screamer.

Go may not be your cup of tea if you don’t like progressive rock, but if you want to know what they were up to, check out the ponderous, experimental “Crossing the Line” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T3lDZ9MPFLs ) – hopefully in its position in the full LP rather than chopped free of its intro as with this link. Check out the more conventional “Winner/Loser” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBup2yMtME8 ), based on the philosophy behind the ancient Asian board game they also call “Go,” which is what the LP is more or less about.

While Winwood wrote words and music to the above-mentioned “Winner/Loser,” it’s hard to know how many of the themes expressed in his musical library should be presumed his own. He has partnered with poet/songwriters Vivian Stanshall and Will Jennings, and most notably with his career-long friend and Traffic co-founder Jim Capaldi (1944-2005). Yet esoteric topics permeate so many of Winwood\’s musical involvements that it seems hard to separate him from them.

“Roll Right Stones” seems sensitive to the supernaturalism of the ancient megalithic monuments. If the great mythologist Sir James George Frazer had to pick a single one of the deceptively simple British ballads to symbolize all his themes, Traffic’s re-adapted “John Barleycorn” would be it. The haunting, fantastic “40,000 Headmen” has likewise been likened to the ballads of Winwood’s British ancestors. “Hidden Treasure” displays a Zen-like spirituality that would have been quite familiar to the Romantic nature poets. The enigmatic rocker “Dear Mr. Fantasy” would seem to address the position of the performing artist within society. A jazzy mood-piece (“Dream Gérard”) tributes the French surrealist author Gérard de Nerval. These are the signs of a musician crossing into other disciplines, as well as trying to lead us all to that higher level.

Mr. Winwood, I wish you a happy late birthday. My tribute to you is so many years overdue that a few extra days in 2020 shouldn’t matter. When I was a young man trying to find my voice in this world you were one of my inspirations among living artists. Thank you for sharing your talent with us all.

© 2020 Mason Winfield