[The fairy lore of the British Isles may be the liveliest such tradition recorded. Some of its numberless, colorful supernatural beings are portrayed as solitary. Others live in communities, even kingdoms. Some are one-offs, famous enough to be named, while some are mere figures of a type. Some dwell in nature or in ancient constructions like burial mounds. Some dwell among humans in houses or barns. Some are shapeshifters and magicians, and some are fixed in a single form and have modest powers. Some are kindly, some are malevolent, and some can be either. Any one of them is powerful enough to be dangerous.]

Scottish author Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) may be most celebrated as a novelist. People properly remember him for historic adventures like Ivanhoe and Rob Roy. He was also a poet, the composer of long verse romances like Lady of the Lake and Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805) – in whose footnotes the strange episode of Gilpin Horner may be found.

The “Lay” (a storytelling poem) is a 17th century adventure set in the Border region of Scotland. It features knightly combat, desperate lovers, supernatural characters, magical shapeshifting, and other features of the classic medieval-inspired romance. One of the Lay\’s odd characters is Gilpin Horner, a goblin once controlled by the legendary Scots wizard Michael Scot (1175-1235).

Sir Walter’s spellcasting goblin is an influencer of plot action like Shakespeare’s Puck/Robin Goodfellow – or Ariel – and finally recalled by the spirit of his former master, Michael Scot. Sir Walter seemed abashed for some reason about including the rude figure in his work, confessing that he did so at the urging of a prominent lady who wanted him to work a local legend into his creation. In the copious footnotes of the “Lay” he details the inspiration for Gilpin Horner.

Around 1800 an unnamed gentleman of the Scottish Borders sent the author the testament of “Old Anderson” reporting a long encounter with an apparently supernatural being. This Anderson had lived his whole life by Todshaw Hill (a short drive southwest of Selkirk) in Eskdale Muir (about ten miles northeast of Lockerbie). While too young to have experienced the wonder himself, Anderson had heard it discussed many a time by people who had, including his father. None had any doubt that the story was true. In summary:

One evening presumably in the early 1700s, two men were out tending to horses in a part of rural Scotland near today’s united council area of Dumfries and Galloway. One of them heard a moving voice in the distance crying out repeatedly and possibly despairingly, “Tint! Tint! Tint!” Now, “Tint” is a Scots way of saying, “Taken,” which could mean a number of things, but said like that it most likely would mean, “Possessed by the Devil or the Fairies.” That’s the way the pair took it. Possibly suspecting either a joke or someone in need of help, one of them, a man named Moffat, called out, “What deil (devil) has tint ye? Come here!”

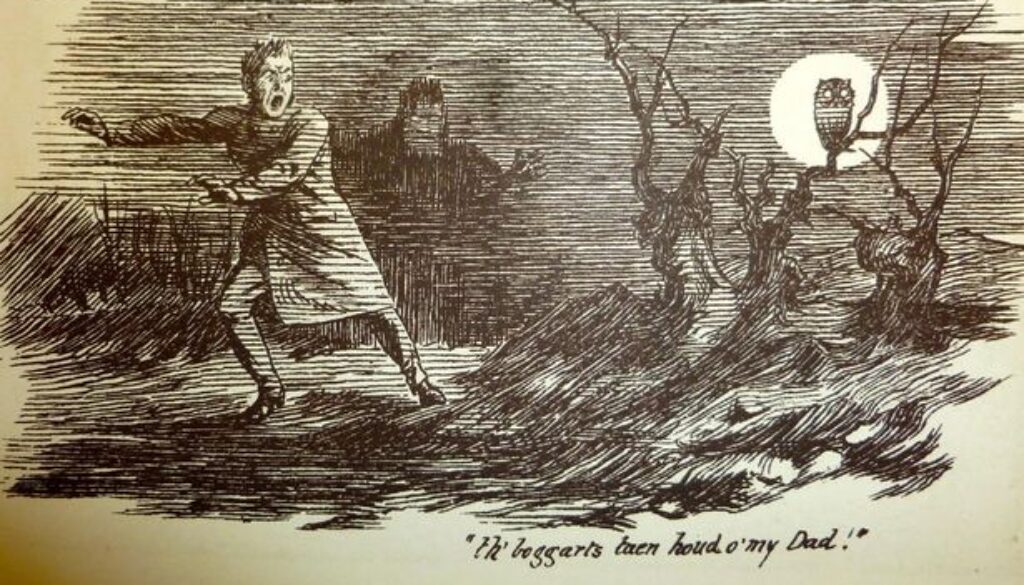

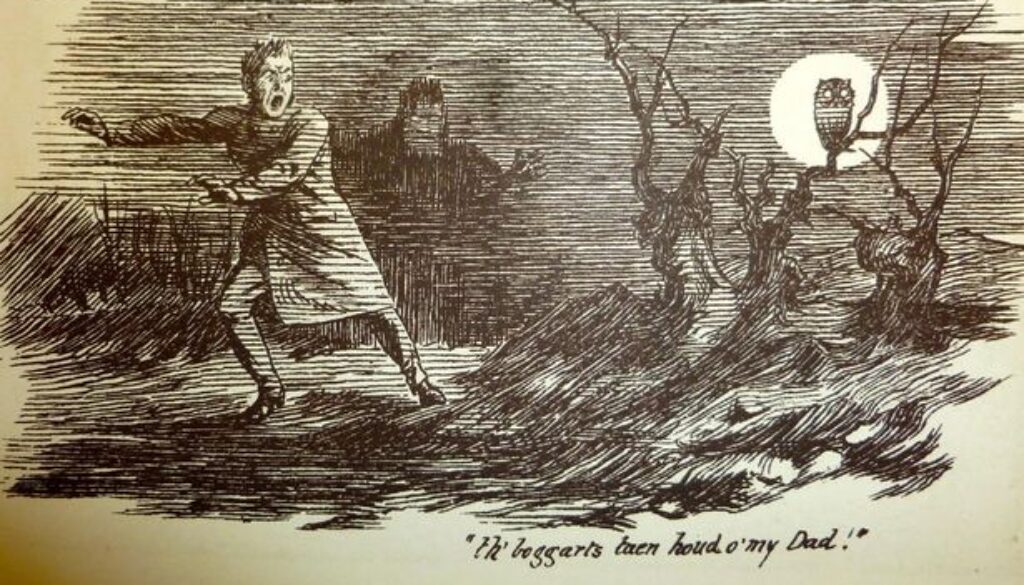

Something small and humanlike very quickly appeared. The second the pair laid eyes on it, they took it for nothing other than a figure out of their own folklore – some sort of goblin that they might call a boggart or a bogle. They took off running back to the home of farmer Moffat. The creature ran with them, and, when Moffat fell, ran over him, apparently right over his back. It was waiting at his house when he arrived, and it stayed with the family long enough for most of the community to get a good look at it.

Everyone in the farmer’s circle was too afraid of the critter to say boo to it, and it had the run of the Moffat house and farm. It had an ugly face, and its limbs were said to be “misshapen.” It had animal-like speed and elusiveness, but it doesn’t seem to have worked any magical feats. “It was real flesh and blood,” wrote Scott\’s witness. It ate and drank. It was especially fond of cream and could put away an uncanny quantity when people let it.

It also had a mean streak. When it found that it could buffalo any of the Moffat children, it scratched and tormented them without mercy. In fact, one time the farmer walked in upon it mistreating one of his children and lost his cool with it, giving it a shot that set it rolling and tumbling like it had been pitched off of a train. When it came to rest and shook itself off, it perked up its head and said, “Ah hah, Will o’ Moffat, you strike sair (hard)!”

Other than the critter seeming to learn its lesson about bullying, things went as they had for a time after. One evening, though, when the women were milking the cows and the chastened goblin was playing with the children, everyone heard a loud, shrill voice from somewhere near them cry out, Gilpin Horner! Gilpin Horner! Gilpin Horner!

At that the critter perked up its head, said, “That is me, I must away!” and almost immediately “disappeared.” Whether that means “magically vanished” or “made tracks quickly” is irrecoverable now. The being who answered to the name was seen no more. Thus ends the fairly cryptic account.

Stories build upon stories. We\’ve always known that. But I\’ve always thought that there had to be something at the root of every legend, and I would have a hundred questions to ask of anyone who had gotten a look at Gilpin Horner or had any more information about it. What was its skin tone? Was it clothed? How big was it? Could it fly or did it simply run fast? We see that it could speak, but how intelligent did it seem? Did it ever say anything about its origins? Did its entrance and exit take place at dusk that, like dawn, was the typical Celtic witching-hour?

The fact that the critter – like most ambiguous supernaturals – needed an invitation to join the human community is suggestive. Note that it was Moffat who first called out to it, and it was his household it joined. Suggestive, too, is the triple-call reeling Gilpin Horner back, presumably, to its master. Three is a sacred, symbolic number all over western tradition, and both prayers and spells often needed the third gesture to be complete. Yet in the words of its observers, the creature was as material as anything else on this earth.

We often stereotype the folk of earlier centuries as highly superstitious, believers in almost any untoward subject. I think this is overdone, at least in the period of this tale. Every age has held both the superstitious and the skeptical. It\’s probably only the balance – and the subject – that changes as we move toward the present. People know what they see. Not every strange thing they say is made up. I believe that now and I believe it of then.

It’s still not often that a figure steps out of storytelling and into paranormal report, becoming something at least one person attested to have witnessed. It’s hard not to think that with Gilpin Horner we may have had something out of the average.

Mason Winfield © 2020