The Wight o’ the Stane

An enormous supernatural tradition has built up around the ancient earthworks. In England, they say Merlin built Stonehenge with his spells. A formation of standing stones – Long Meg and her Daughters – were a coven of witches turned into stones by Scottish wizard Michael Scot. The Cerne Abbas hill figure (a gigantic chalk carving) was a Danish giant who’d come to invade England. Another hill effigy, the White Horse of Uffington, could be the dragon killed on the spot by St. George. It was no different in other Celtic countries, including dragon-legends about Mont St. Michel in France and fairy-king tales from a barrow near Dublin, Ireland. The legendry of witches, Little People, giants and spirits is almost everywhere considered completely folkloric. On the last night of June 2007 I met a living witness whose rendition may unwittingly confirm it.

After a ghost walk on the last Saturday of June, I ended up at a backyard party in the village of East Aurora, NY. One of the hosts introduced me as “the ghost guy” to a British couple by the wine bar. That provocative title seemed to bring a lot out of the woman, by far the more talkative of the two.

This very intelligent woman commenced a conversation that I would call “assertive.” Equipped both with strong skepticism and the worst stereotypes of people in “the ghost business,” she presumed that I held all the wildest paranormal beliefs we ever hear about; that all paranormal subjects are the same inextricable mess, as if stewed together in a gumbo; and that no paranormal subject has any shred of truth or value. She raised, then challenged, one ridiculous idea after another and cut off each response by going to the next.

I was glad to go through the pros and cons of each matter to the extent I could, and we were all quite friendly. Evidently whatever I said made some sense, because she sent my website an e-mail, hoping to bring her British mother to a ghost walk when she’s in town. Her husband – quiet during all the grilling – chipped in an experience of his own that night that was one of the most profound I heard that year.

When he was in his late teens he’d served a spell with the British Army. He was on “bivouac” – we call that camping – in the hills of the Lake District with two of his mates, and they’d seen something late one night that really turned them around.

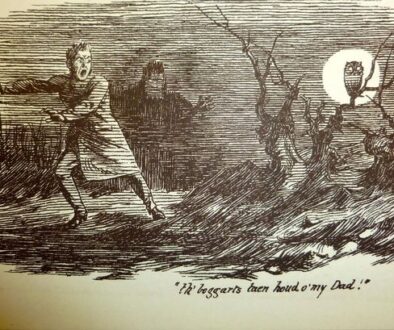

As the three sat on their hillside, looked down over the small field below them and wondered how to keep themselves entertained and warm, they saw a dark-clothed figure cross the scene in the moonlight. This was odd in itself. They were out in the middle of nowhere; casual night-walkers were seriously out of place.

Odder yet was the man’s appearance. He had on a long dark coat and a broad-brimmed hat of a distinctly non-contemporary style, almost a high-pointed, wide affair we call “a witches’ cap.” Oddest of all, he moved deliberately into the open space, shot a glance up at all three of them, and then vanished as if he’d walked into a hole behind the air. Shocked, they all ran down to where he was when he was last seen. The spot was easy to find. There was something already there – an ancient, man-sized standing stone, a menhir, that could easily have been in place for five thousand years. It was as if the man they had seen had stepped behind the stone and vanished – or stepped into it as if it was a phone booth. All three of these young men saw the same thing, and all were terrified. They spent a sleepless night on the hill.

This 1990s report was straight out of Celtic tradition. So many of the stones and sites have lore and legends about them, and the notion that a “Spirit,” a wizard, a Fairy-being, or some other power-person could somehow inhabit one of these stones or its location is far from new. It was a fixture of British Isles tradition. We need only remember Tolkien’s sinister “barrows-wight” – a malicious being that inhabits a burial mound and troubles the four questing hobbits. The idea that the stones or circles represent portals into other dimensions is not far from the mainstream of New Age custom.

One of our contemporaries – Ohio mystic Ken Harsh – would not be surprised at all by this experience, though he might quibble with the imagery, at least in the Americas. Ohio and upstate New York are distinct for the type of earthworks most similar to those left by the megalithic culture of Europe: simple mounds, geometric forms, and human and animal effigies. A frequent speaker at Lily Dale, Harsh has plenty to say about the ancient earthworks of the Americas. He’s almost the single-handed spiritual preserver of some of the ones in his midwestern state, and he preserves the traditions of others.

For Harsh, every ancient sacred earthwork has its own presiding spirit. Whether it’s the spirit of a dead human, a dead community, or even a supernatural being still technically as living as it ever was, Harsh does not specify, or did not when I heard him speak at Lily Dale in 2004. He has, however, developed a wondrous reverence for these old earthworks, and a modern method of approach guaranteed to ensure respect for the site and growth in the approacher.

Let’s go back to the apparition the three young men saw. The male figure’s hat and general look was reminiscent of the traditional “wizard” in popular entertainment. We should stop and wonder if this image seems contrived to us. Entertainment witches and sorcerers from Walt Disney to Gandalf to Harry Potter have worn robes and broad-brimmed, often pointy hats. There’s a reason the books and movies picked that image for us: because it was to some extent valid. There was a standard look to the real power-people. The Celtic Druid’s customary garb was a hooded robe, often heather-blue. And that pointy-hat was a traditional sorcerer’s cap in Europe for thousands of years. (One of the Indo-European mummies found in the Altai region of China had such a hat, and it was deduced from it that he was a wizard.) And wizards, witches, druids and fairies have always been associated with the stones.

As for the title of this piece… A “wight” is a simple Middle English word for a living creature. It’s a being, a critter, a human, anything with a life in it. The German and Scandinavian versions of the word-root aren’t all so character-neutral, in fact, leaning to the sinister. You’ll find the word in the ballads of the British border with Scotland, too, that were recorded long after Chaucer’s day. Since the old Scots tended to drop consonants at the end of standard English words and put “a” in place of “o” in many others, “The Wight o’ the Stane” seems a good title for this piece. I still don’t know what to make of the experience, as if the old Druids of the Isles could still be extant, playing their tricks and letting us know they are still with us. That’s the most hopeful explanation for what these three young men saw.